'Tales my Mother Taught Me'

Steinbeck’s mother, Olivia, was a teacher in California who recognised the importance of stories. She also knew her Bible well, told her son Bible stories from the age of three and was obviously a good story-teller because Steinbeck demonstrates similar gifts for writing, not least in his two major works, The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, both bristling with biblical illusions which Steinbeck regarded as very important, and parts of which closely resemble the style of biblical Hebrew.

Steinbeck grew up in a world which was essentially Protestant and biblical or (to be more precise) Episcopalian, and the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. His parents were loyal Episcopalians and the KJV was the official version for the vast majority. The Episcopal Church was part of the Anglican Communion and the direct descendant of the Church of England, the child of the Protestant Reformation. The KJV was also the child of the Reformation but its parentage was not entirely straightforward. It was not simply Protestant rather than Catholic but the fruit of internal dissent between traditional Protestants and radical Protestants, with the Church of England on the side of the traditionalists who came out on top. The result was not so much a change from the authority of the Church (Catholic) to the authority of the Word (the Bible), as an assertion of authority for the Word but still under the control of the Church (but now the Church of England), thereby confirming the rejection of the Papacy on the one hand and neutering the excesses of the more radical and independent branches of the church on the other.

To achieve this the chosen instrument was a royal commission (James 1) to produce a fresh translation to replace all other translations in circulation and to declare it ‘authorised to be read in churches’. In fact, it was not so much a new translation as a revision of an earlier translation by William Tyndale; it did not replace other translations, the earlier essentially Protestant Geneva Bible retaining its popularity; it was nearly a century before it achieved any kind of general acceptance and though it acquired the title of ‘Authorised Version’ it was in fact never ‘authorised’ as a translation by anybody.

Much has been written about the quality of its language and its effect on the English language down to this day. What is sometimes overlooked is its close adherence to the Hebrew style, grammar and syntax, sometimes described as ‘timeless English’ or ‘the language of the people’, following Tyndale’s commitment to produce a text which would enable the boy who drives the plough to know the scriptures. The KJV translators set themselves to match that simplicity with academic rigour, adequately representing the Hebrew and suitable for reading in public. Hence the emphasis on simple words (Anglo-Saxon rather than Latin) short sentences, pauses, and a rhythm which facilitated memorisation.

Steinbeck therefore grew up in a family under the influence of a church which represented a genteel respectability (as reflected in the Hamiltons in East of Eden) with a profound Protestant respect for the Bible, alongside a superficial if not paternalistic awareness of others (Cannery Row and Tortilla Valley) and a very limited appreciation of their way of life; certainly not a radical Christianity.

Life in the Wilderness

Against the background of the Dust Bowl and the migration of the Okies to California in search of a better life Steinbeck’s mother must surely have told him the Exodus story: a depressed and threatened people in search of a land ‘flowing with milk and honey’ (Exodus 16: 31; Deut 8: 8). The Israelites were slaves in Egypt with a harsh Pharaoh determined not to let his people go. Moses was an uncertain and unwilling leader. Once they escaped they were subjected to one hazard after another, never sure where they were or where they were going, turning this way and that, always on the move, always believing and hoping there was a better life somewhere else but never quite able to find it.

The Grapes of Wrath is virtually a re-run of the Exodus story with an uncertain and unwilling preacher, the creation of basic rules for the community on Highway 66 (almost human rights) not unlike the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20), and a title which echoes Ezekiel 18: 1-5, but there is much more to the story than superficial repetition of details and a few biblical references may suggest.

The biblical story of the Exodus is an experience of wilderness, and at more than one level. At one level wilderness is literally land. Highway 66 is the Judean wilderness, harsh, unwelcoming and barren and like many an Old Testament character Grandpa (in The Grapes of Wrath) prefers to live and die on the land to which he belongs.

At another level, it is a universal human experience, a major component in the journey of Israel from slavery to freedom and the Pharaoh can appear in many guises, such as the impersonal power of the banks and all those other institutions (including the church) which are more concerned with the preservation of their own position than the needs of those whom they exist to serve.

Next comes the slavery to the dream, and the hope of freedom which, when (or if) it comes is never quite what one expected. For the Jews it was forty years in the Judean desert, where the real challenge was not so much the harsh terrain as the pain of living in ‘space far away from ordered land’ and intensified feelings as the geographical and the emotional worlds coalesce to produce feelings of lostness, danger without protection, fear without security.1

These are the unfulfilled hopes Steinbeck identifies in the case of George and Lennie in Of Mice and Men and in the conflicting emotions in The Red Pony, with Jody’s water-tubs and the black cypress, ‘opposites and enemies’, one a place of comfort the other a place of hostility,2 not unlike the rock as a hiding place (Exodus 33: 22) and the anxiety as Moses strikes it (Numbers 20: 8,10-11).

With this goes what Steinbeck describes as ‘westering’. The lot of the Children of Israel (Numbers 33: 5-37), was to travel but never to arrive, reflected in more than one Steinbeck story, but spelt out in The Red Pony, when Grandpa (‘the leader of the people’) describes the journey westward with the thrill, the vision, the hope and expectation. and the vision of a new day. ‘It wasn’t getting there that mattered, it was movement and westering’, and ‘the westering was as big as God’.3

Such wandering in the wilderness is more than coping with personal hardship and ‘westering’ in an unwelcoming environment. It is also a quest from self-seeking individualism to a more healthy relationship between individual and community, a problem with which the Jews wrestled for some 500 years before achieving something of a denouement with Ezekiel (18: 2), whence the title ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ is a straight lift.

The One and the Many

Five hundred years prior to Ezekiel life for the Children of Israel was essentially community based and the relationship between the individual and the community very different, much more akin to the kind of community Steinbeck grew up in where individuality was not to be coveted but to be sacrificed in the interests of the common good. Childhood reading led him to nurture and expand his individuality but as he grew older and developed an interest in Transcendentalism4 its emphasis on the individual as opposed to society left him with the difficulty of sorting out the relationship between the one and the many.

On the one hand he was no doubt well aware of Israel’s community-based world, where one man offends but all are guilty,5 and on the other by Ezekiel‘s challenge to the proverb that ‘the fathers have eaten sour grapes and the children’s teeth are set on edge (18: 2) with an affirmation that ‘a child shall not suffer for the iniquity of a parent . . . the soul that sinneth it shall die’. (18: 20).

Some biblical scholars have suggested that the Jews solved the problem by a fluidity of thought between ‘the one and the many’ so that it is not always clear to later readers which was intended.6 Steinbeck may or may not have been aware of this (probably not) but his resolution of the tension was not dissimilar.

In a letter to George Albee,7 for example, he hints at the notion of religion as a phalanx emotion comparable to the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2: 1-12), when a rushing mighty wind took hold of a vast congregation and changed their lives, and he can write approvingly of Grandpa’s ‘westering’ in T, but then when writing In Dubious Battle8 he worries about how easily a person may lose (or surrender) individuality and be taken over by a mob. His conclusion (also like the Jews not altogether convincingly) is that

‘ . . . man is a double thing — a group animal and at the same time an individual’ (and) ‘he cannot successfully become the second until he has fulfilled the first.’9

What he never doubts, however, (again like the Jews) is the broad direction in which he is moving. ‘Westering’ (for Steinbeck) and Pentecost (for Christians) are but gateways for individual and community as they work their way from the self-seeking, individualism of Babel (Genesis 11: 1-9), through ‘the one and the many’ in Hebrew thought, to a discovery of a more healthy relationship between individual and community with the common language of Pentecost. (Acts 2: 1-12).

From Babel to Pentecost

Between Babel and Pentecost lay a thousand years of Jewish hopes and aspirations, disappointments and rejections and for Christians at least Pentecost proved to be more the end of the beginning than the beginning of the end. Not unlike the American Dream,10 there were times when it flourished and hopes seemed high and other times when the outlook was gloomy. Steinbeck was writing in one of those gloomier periods when, if not actually under threat, the concept was being questioned. Crucial questions would not go away. Traditional answers failed to satisfy. Where did it all go wrong? How might it all have been different? And does it have to be like this, or have we a choice?

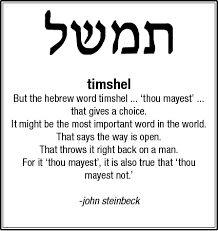

At the heart of East of Eden lies this concept of timshol (Genesis 4: 7), focusing on an interpretation of this one Hebrew word: ‘Sin is lurking at the door; its desire is for you, but timshol.’. What does it mean and how is it to be translated? English translations speak with a variety of voices according to the translators’ theological viewpoint. When ‘sin crouches at the door’ one says ‘you must resist it’, another says ‘you will be its victim’ and a third says ‘you can (or should) resist it’.

Steinbeck comes up with the shrewd alternative (‘you may’). Not a command, not a threat, not even a pious hope, but an open door, thereby fortifying his conviction that a man may free himself of his past and conquer evil. Whether it is a legitimate translation of the Hebrew has been much questioned, but Steinbeck consulted a rabbi friend who said it was OK and a distinguished Hebraist acquaintance of mine assures me that the rabbi was right.11

The World of Myth

Still apparently not altogether satisfied with his answer Steinbeck headed for England to explore the world of myth in the work of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, a copy of which his Aunt Molly had given him when he was nine and he had never stopped ‘working and studying this recurring cycle’.12 Surely this would help him to clarify the beginnings of it all. Unfortunately it failed and left him with one book he never completed but with an experience which focused for him a clearer understanding of myth and the place of Jesus.

Following the assassination of John Kennedy in 1964, Steinbeck used the word ‘myth’ to describe Kennedy in a letter of sympathetic appreciation to his widow. Sensing that she took exception to it, he felt the need to explain what he meant by myth.13 To him, people like the Buddha, Jove, Jesus, Apollo and Arthur were all ‘myths’ — not that they didn’t exist but because within themselves they embodied characteristics and concepts such as authority, heroism, pride, and victory which are eternal and, in a day when such characteristics are lost (or forgotten), they need to be brought out occasionally and verified by the Hero. Such ‘heroes’ have become icons rather than people as we know them.

It is significant that he includes Jesus. Three days later he followed it with a second letter14 to reassure her that her husband’s work ‘was not a lost cause’ because ‘all of us carry a fragment of him’ (JFK) which he defines as the quality of goodness. He then switches immediately to Jesus and the cry of dereliction, lama sabachtani (Matthew 27: 46; Mark 15: 34), adding ‘in that one moment of doubt we are all related to him’ (Jesus); then In a third letter15 he explains how only then can we go on to say, ‘Father into thy hands . . .’ (Luke 23: 46). ‘Who has not had the first cannot have the second.’ One can only wish he had produced his ‘Life of Jesus’ (which he contemplated but never wrote) and hazard a guess as to the way he might have further enriched our understanding of the Bible and the Christian faith.

Other Stories

With his detailed knowledge of the biblical material Steinbeck writes in such a way as frequently to turn our attention to the Bible and to challenge familiar interpretations.

East of Eden is nurtured and matured in the origins of good and evil (Genesis 4: 1-16), with carefully chosen alliterative names (Cain and Abel, Adam and Charles, Caleb and Aron)16 and an imaginative and creative interpretation of timshol (Genesis 4: 7) which led Samuel, ‘a fire-eating Irish Protestant’, to want to be a better fellow.17

Jesus told a story of a man seeking goodly pearls and prepared to sell everything he had to acquire one, presumably as an example of single-minded commitment (Matthew 13: 45-46). Steinbeck reminds us of the story by his title (The Pearl) but with a new twist taking us to Caesarea Philippi (Matthew 16: 25) where salvation comes not by selling everything to acquire the secret of life (the ‘pearl’) but by discovering what it means to throw it away.

Paul, arriving in Athens and shocked by Greek idolatry (Acts 17:16-32), focused on one altar with the inscription ‘to the Unknown God’ (v 23) as the basis for a sermon with the words, ‘Whom therefore you ignorantly worship, him (Jesus) declare I unto you’. Steinbeck, obviously familiar with the story, entitles one of his books ‘To a God Unknown’ but makes it abundantly clear that ‘the transposition in words is necessary to a change in meaning. The Unknown in this case means ‘Unexplored’ . . . I want no confusion with the with the unknown God of St Paul’.18

Jesus talked a lot about the kingdom of God, with stories of strange people, miracles, surprise endings, and demands which were so sensible, reasonable, and to which none could object but which were clearly unrealisable. Nobody lives like that. But here and there Jesus found people who did and enabled many to surprise themselves. Steinbeck, similarly, in The Pastures of Heaven, introduces us to people like many in the gospel stories he must have heard in childhood; people who ‘trade’ in a different way to the point where we even envy them, only to be surprised that they actually envy us.